What is Tracheal Collapse?

The trachea (windpipe) is a large tube that is reinforced by cartilage rings. The trachea runs alongside of the esophagus (food pipe) and delivers air to the lungs. Tracheal collapse is a clinical condition associated with blockage of air flow to the lungs from weakening of the cartilaginous rings of the trachea. When these cartilage rings become weakened, they become flattened to varying degrees (Figure 1) as an animal breathes in (inspiration) or out (expiration). The location of the tracheal flattening can occur within the chest (on expiration), in the neck (on inspiration), or both inside and outside the chest (so that both breathing in and out are impacted). In many dogs with tracheal collapse, the smaller breathing tubes within the lungs (called the bronchi) are also flattened, which can impact treatment and response to treatment.

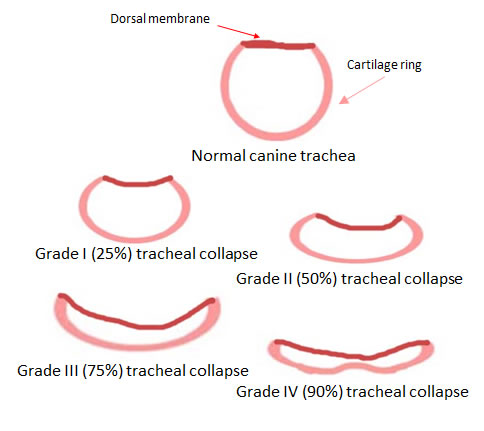

(Figure 1)

Figure 1: The degree of tracheal collapse, or flattening, can be graded in severity from I to IV, with IV being the most severe. Dogs with only minor collapse may not have any clinical signs, while dogs with more severe collapse may have severe cough or even distress when breathing because the collapsed trachea does not allow normal airflow.

Tracheal collapse is most commonly seen in small and toy breeds such as: Chihuahuas, Pomeranians, toy poodles, Shih Tzus, Lhasa apsos and Yorkshire terriers. Signs usually begin in middle-aged dogs and may worsen as the dog ages, but sometimes signs begin in old or young dogs.

Clinical signs of tracheal collapse include:

- Chronic, harsh, dry cough that is often described as sounding like a “goose honk”

- Coughing with excitement, stress, or exercise

- Coughing elicited when being picked up and or when pressure is applied to the neck

- Vomiting, gagging, or retching in association with the cough

- Difficulty breathing

- Wheezing

- Cyanotic (turning blue) episodes/collapse

(Video 1)

Video 1. Animation demonstrating the dynamic nature of tracheal collapse. Cervical (neck) trachea collapses during inspiration (breathing in) and expands during expiration (breathing out); thoracic (chest) trachea expands during inspiration and collapses during expiration. Animation provided courtesy of Infiniti Medical LLC, Menlo Park, California.

How is Tracheal Collapse Diagnosed?

The first step to diagnose an animal with a collapsing trachea is to take radiographs. Radiographs are a good, noninvasive imaging modality that can sometimes identify a collapsing trachea. It is important to note that radiographs do not diagnose 100 percent of the cases because the trachea is not flattened at all times, and a radiographic image only captures a moment in time. Because the trachea is not always collapsed, other diagnostic tests may be required.

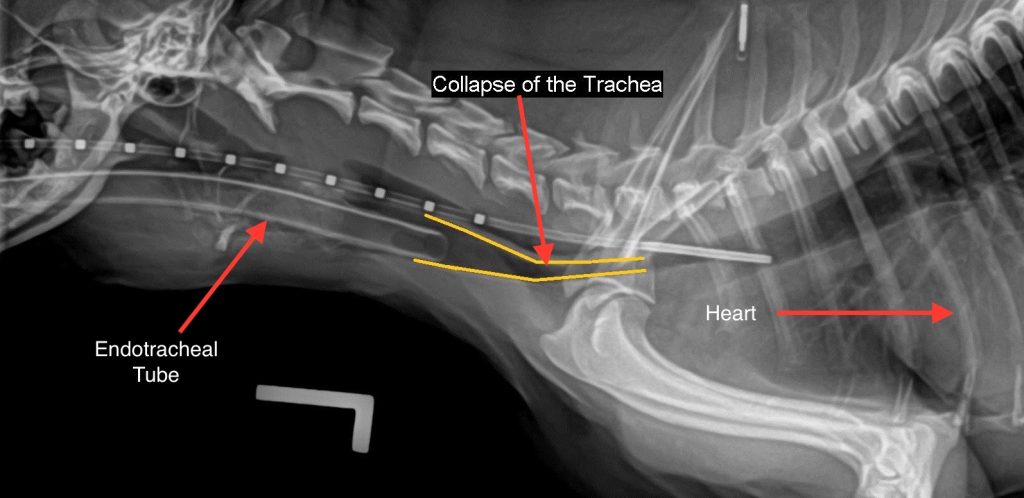

(Figure 2a)

(Figure 2b)

Figure 2a and 2b. Radiographic image of a normal dog (a), and a dog with tracheal collapse (b). In each radiograph (x-ray), a portion of the dog’s skull is seen on the left. The spine runs along the length of the image from just behind the skull to the right of the radiograph. In the normal dog (a), the trachea is seen as a tube of approximately equal diameter all the way from the larynx (at the back of the throat) into the chest. The inside of the trachea is very dark in color because air shows up as black on radiographs. In the dog with collapsing trachea (b), the same structures can be seen, as can two pieces of medical equipment. Because this radiograph was taken while the dog was under anesthesia, you can also see an endotracheal tube inserted part way into the trachea to give the dog gas anesthesia, and a measuring tool within the esophagus extending past the endotracheal tube. The yellow lines outline the narrowed trachea where it enters the chest from the neck. This portion is said to be collapsed.

Fluoroscopy is an imaging modality used at many universities or specialty hospitals. Fluoroscopy uses X-rays to obtain real-time moving images as the patients breathe. It can also be used to see what happens during an animal’s cough to determine where the collapse may be occurring.

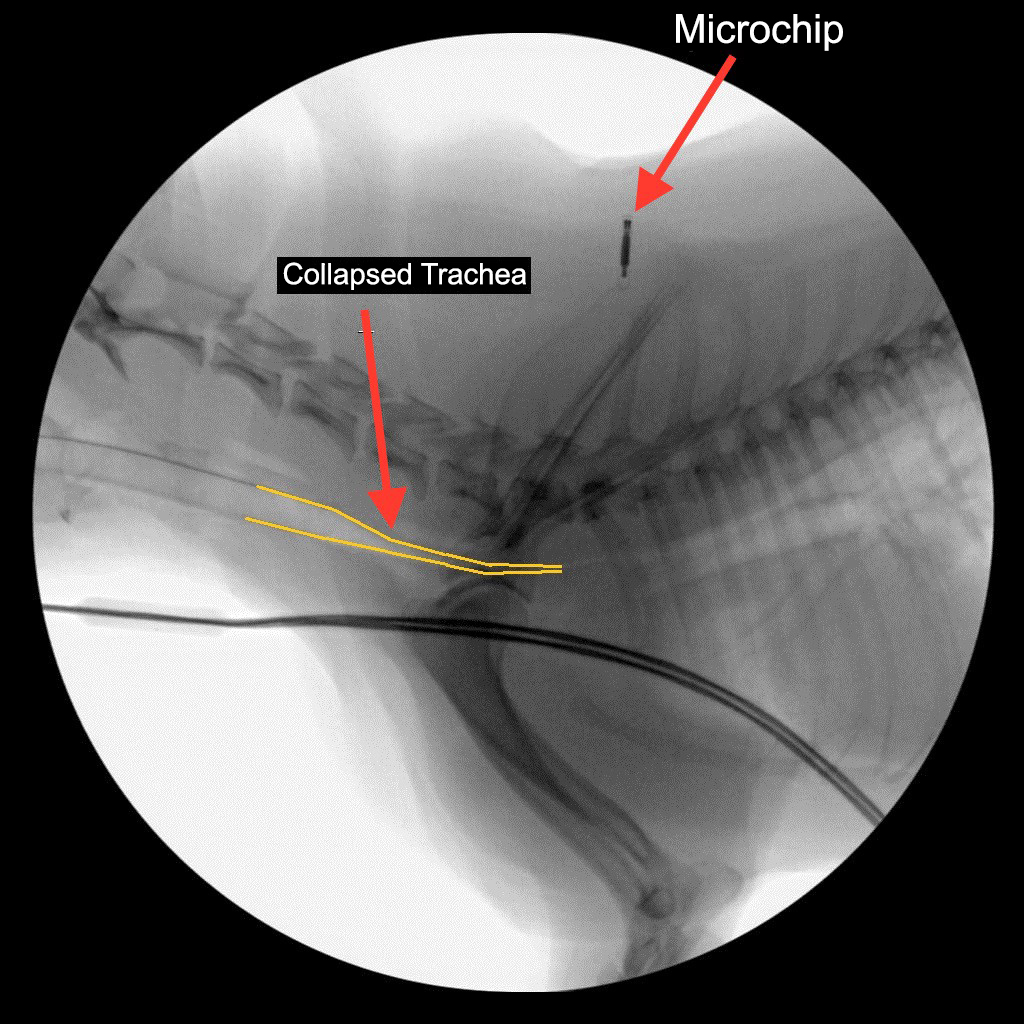

(Figure 3)

Figure 3. Fluoroscopic image of tracheal collapse. This is a still picture captured from a short video clip. In this image, the yellow lines outline an area of collapse where the trachea enters the chest from the neck. You can also see a microchip that has been placed between the dog’s shoulders; this chip contains contact information to help reunite lost pets with their owners.

Tracheoscopy/bronchoscopy is a procedure that allows your doctor to look at your dog’s airway from the inside. A thin viewing instrument called an endoscope is inserted through the mouth and into the trachea and bronchi. This procedure requires anesthesia, but allows the most complete evaluation of the airways. Tracheoscopy/bronchoscopy also visually identifies any inflammation or irritation that may be present in the patient’s airways associated with infectious diseases or chronic coughing, and allows the veterinarian to collect samples for bacterial culture and microscopic evaluation.

Treatment Options: Medical Management Versus Tracheal Stents

Medical management should be centered on efforts to minimize coughing and control airway inflammation. Environmental modification and reduction of stress on the respiratory system are important components of any treatment. If the dog is overweight, a weight loss program should be undertaken. Reducing everyday stress and excitement, improving air quality within the home (for example, eliminating exposure to cigarette smoke), and use of a body harness instead of a neck collar are all things that can decrease the frequency of symptoms caused by tracheal collapse.

Depending on the degree and progression of the disease, as well as complicating factors like chronic bronchitis, your veterinarian may employ the use of cough suppressants, anti-inflammatory medications, or sedatives. Sometimes, a short course of antibiotics is also used to treat complicating infections. It is important to keep in mind that a collapsing trachea is a progressive and irreversible disease. At some point, the disease may progress to the point where medical management becomes ineffective.

Table 1: Drugs commonly used in the treatment of collapsing trachea

| DRUG CLASSIFICATION | SPECIFIC DRUG | COMMENTS |

| Cough suppressants | ||

| Hydrocodone | Though very effective, this is a controlled substance. Your veterinarian can only prescribe a limited amount at a time. Will have sedative effects, especially early in treatment. | |

| Butorphanol | This too is a controlled substance drug. Will have sedative effects, especially early in treatment. | |

| Lomotil | May cause constipation or sedation and should be used with caution in certain breeds. Can impact normal mucus clearance. | |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||

| Prednisone | A steroid that may cause increased drinking, urination and hunger. | |

| Fluticasone | An inhaled steroid, this has fewer systemic effects than steroid pills or injections. | |

| Antibiotics | Various types (eg. tetracyclines, azithromycin) | Antibiotics do not treat the tracheal collapse, but may clear up secondary infections that complicate the disease. |

For cases where medical management is no longer an effective therapy, a tracheal stent may be life-saving. Most often, a minimally invasive procedure is used to place a stent inside the trachea. Implantable tracheal stents are woven mesh, self-expanding tubes that are inserted within the trachea to provide support to keep the trachea from collapsing. Less commonly, plastic rings can be surgically fastened to the external surface of the trachea to prevent collapse, though this is only useful when the collapse occurs within the neck.

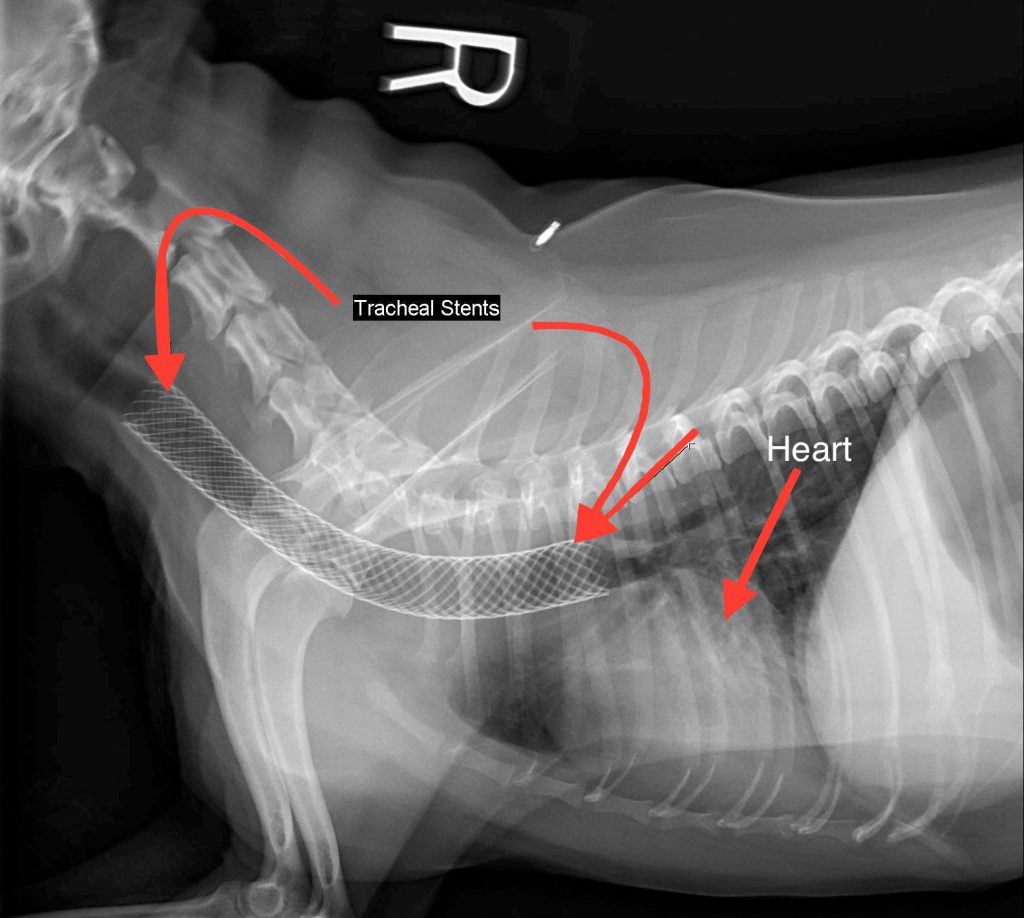

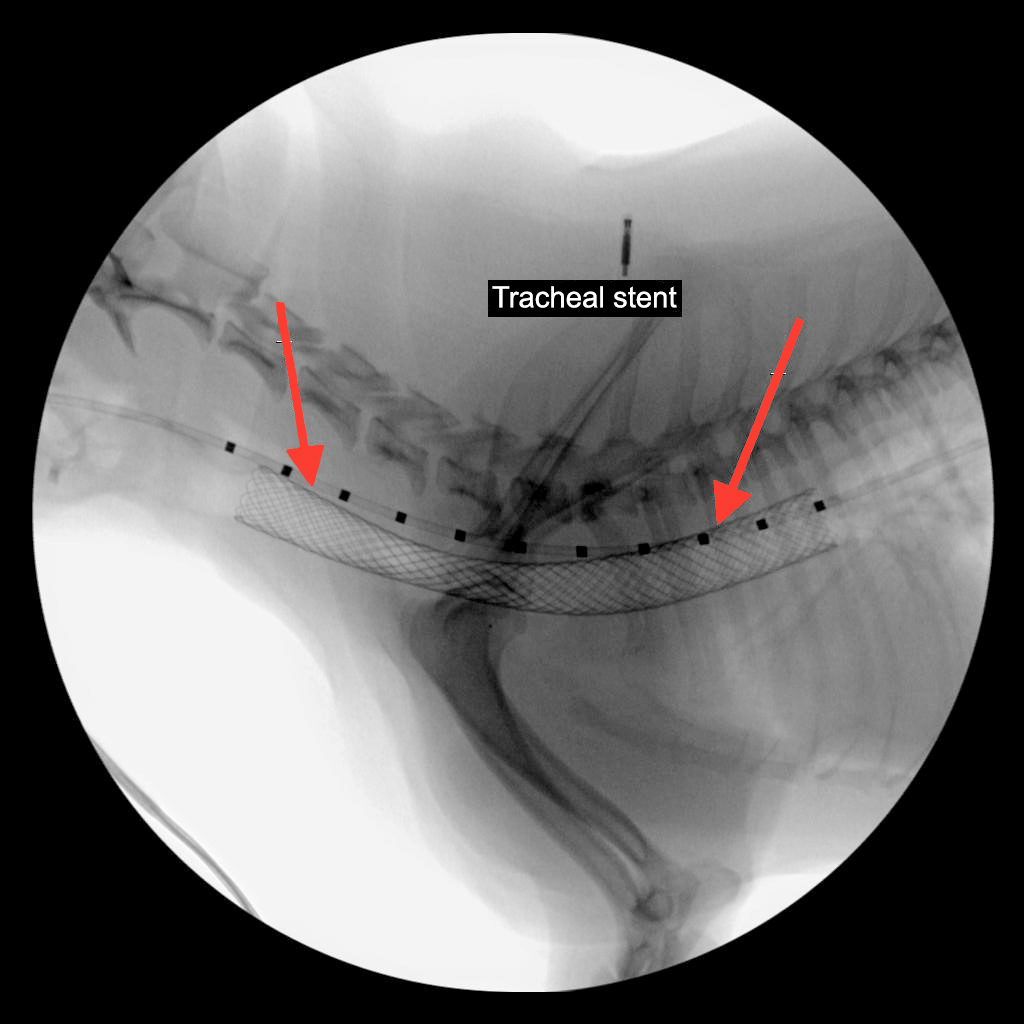

(Figure 4)

Figure 4. Radiographic image of a tracheal stent placed within a dog’s trachea. The woven mesh can be seen inside of the trachea, where it holds the trachea open to keep it from collapsing.

(Figure 5)

Figure 5. Fluoroscopic image of a tracheal stent placed within a dog’s trachea. The wire mesh is positioned during fluoroscopy to ensure appropriate placement in the airway.

The placement of tracheal stents is considered a salvage treatment for tracheal collapse. While it can save lives and improve the quality of life greatly, it does not permanently fix the underlying problem. Generally, patients that are considered good candidates for stenting are those with severe clinical signs that cannot be controlled with medical management. Even after a stent is placed, medical treatment will likely be required. While stents can be life-saving, they may not entirely eliminate the cough. It is also important to know that stents may eventually fail, as the metal stent is not as flexible as a normal trachea.

Tracheal stents are not always a good option for the following patients:

- Have clinical signs that can be controlled with medical management

- <50 percent of tracheal lumen collapse

- Patients with other severe illness

- Patients with severe collapse of the bronchi

- Patients with uncontrolled respiratory infection

Possible complications include:

- Irritation of the airway (which can cause cough)

- Laryngeal paralysis

- Stent fracture

- Granulation tissue formation

- Airway and lung infection

- Stent migration (movement of the stent)

- Tracheal rupture

- Collapse of main-stem bronchi or non-stented regions of the trachea

- Although rare, animals are at risk of death during or after stent placement

What can I expect if I opt for tracheal stent placement?

Tracheal stent placement requires special equipment and expertise. We are pleased to offer this treatment to our clients at the University of Missouri Veterinary Health Center. Typically, we will evaluate your pet with radiographs and or fluoroscopy, but if we are concerned about the possibility of lung disease we may also recommend a computed tomography (CT) scan. This advanced imaging technique gives a much better picture of the lungs and airways than standard X-rays.

Under anesthesia, we will measure the size of your dog’s trachea and choose the closest match to that size in a stent. The stent itself will be deployed with fluoroscopic guidance (real-time moving X-rays) to ensure that it is placed correctly. Frequently, we then use the endoscope to look into the airway, ensure proper placement and collect samples for culture. Your dog will recover from anesthesia in our Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care Unit, where it can be closely monitored around the clock. We will give your dog both cough suppressants and anti-inflammatory drugs in the hospital for at least a day or two after the procedure. Your dog will continue some of these medications once it goes home, at least until the next scheduled follow up appointment. Periodic chest X-rays will be required, and there may be need for repeat tracheobronchoscopy on occasion.

The cost for placement of a tracheal stent at the VHC, including hospitalization and other associated charges, is typically $2000-$3500 for workup, $3200-$3600 for placement and $5900-$6500 for both as of June 2023.

There is no form of treatment for tracheal collapse that comes without possible complications. It is important to discuss these with your veterinarian to develop a plan that is right for you and your pet.

Written by: Abigail LaRosa

Edited: Leah A. Cohn