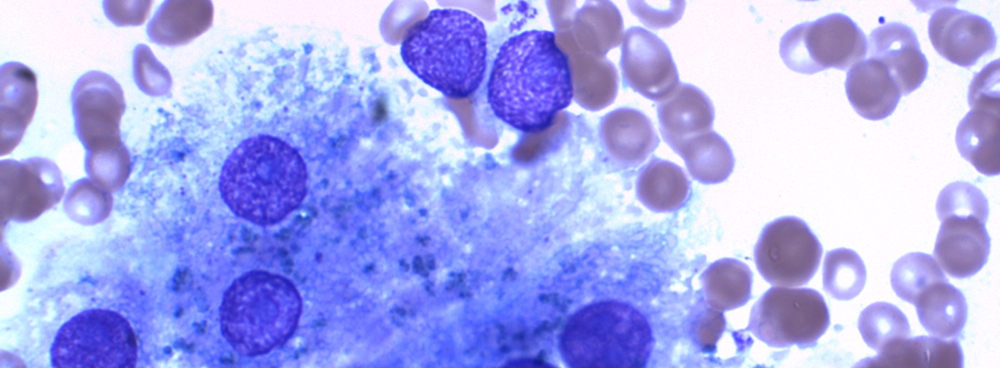

Lymphoma is a common cancer of dogs and cats that can occur anywhere in the body. Lymphoma is the same as lymphosarcoma, as there is no benign variant of the disease. In dogs, it is most commonly seen in the lymph nodes, and in cats common sites are the intestinal tract, internal organs such as the liver and kidneys, and inside the chest. In cats, infection with the feline leukemia virus can lead to the development of lymphoma. In both species, as in humans, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. Chemotherapy is typically well-tolerated, and when patients are in remission, most pets enjoy a normal or near normal quality of life. Common sites for lymph nodes are under the jaw, in front of the shoulder, in the armpit, in the groin and behind the knee.

These are common skin tumors found in both dogs and cats. Their behavior can be predicted by how they look under the microscope. Low-grade tumors typically stay where they grow, but high-grade tumors often spread to other parts of the body. A biopsy is required to determine the best treatment, but surgery is usually the most important step in controlling the tumor. If additional local control is needed, radiation and chemotherapy may be recommended, and if a tumor is high grade and likely to spread systemically, chemotherapy will be recommended with or without radiation. Newer chemotherapy protocols have given more favorable outcomes than in the past, and local control is excellent with surgery and, if needed, radiation therapy.

Dogs and cats can both get tumors inside the nasal cavity. Clinical signs include persistent discharge from the nose on one side, often with blood. Sometimes nosebleeds are seen. The treatment of choice for nasal tumors is radiation therapy. Surgery does not seem to improve survival and may cause more discharge, but it may be used in select cases. Chemotherapy has been tried in a few cases but is not as effective as radiation. These tumors can metastasize, but more often the tumor in the nose is the main problem for the pet. Average survival with radiation therapy is one to 1 ½ years. With no treatment, depending on the clinical signs a dog is experiencing, survival is usually less than six months.

This is the most common bone tumor in dogs. Approximately 8,000 to 10,000 dogs are diagnosed with this cancer each year. Affected dogs are most commonly large- or giant-breed dogs and slightly more often are male. The most common sites are near the wrist and shoulder, as well as near the joints in the hind leg. This cancer metastasizes frequently, as 90 percent of patients have micro-metastasis (spread of small tumors that we cannot initially see on X-rays) at the time of diagnosis. The treatment of choice is amputation, though there are both medical and surgical options for limb sparing, depending on the bone affected. This tumor can also occur in the head and torso and in non-bone tissues. This cancer in cats typically has a much lower metastatic rate, and only about 10 percent of cats will succumb to their cancer during the first year after treatment.

In addition to surgery, because of the likelihood of early spread of disease (metastasis), chemotherapy is important for best survival. With treatment of the affected leg plus chemotherapy, one-year survival rates are approximately 60 percent. At the University of Missouri Veterinary Health Center, we offer novel limb salvage with samarium, which is a bone-seeking radionuclide intended primarily to relieve the pain associated with bone cancer.

These tumors originate from the cells that hold our “parts” together — that is, hold skin on to the body and create muscles and joints. They have a variety of different names but behave in a similar manner. Some common tumors in this group include fibrosarcoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor and hemangiopericytoma. These tumors are often aggressive locally but less likely to spread throughout the body (metastasize). They are treated initially with surgery if possible depending on location. When surgery leaves microscopic cancer cells behind or when a tumor cannot be removed, radiation therapy can be effective. In cats, these tumors have been linked with sites of vaccination or certain injections.