Chemotherapy literally means treatment with chemicals or drugs. This word has become synonymous with cancer chemotherapy in our culture and often provokes an immediate emotional response, stirring up visions of gaunt people with no hair and intractable nausea. While it is true that chemotherapy has side effects, in veterinary medicine most of our patients’ side effects are manageable at home, with fewer than 10 percent having side effects that require hospitalization. As compared to human chemotherapy protocols for similar cancers, many veterinary protocols are less intense. Our goal in veterinary oncology is to offer longer life for animal cancer patients, and to balance that with a good quality of life.

Chemotherapy literally means treatment with chemicals or drugs. This word has become synonymous with cancer chemotherapy in our culture and often provokes an immediate emotional response, stirring up visions of gaunt people with no hair and intractable nausea. While it is true that chemotherapy has side effects, in veterinary medicine most of our patients’ side effects are manageable at home, with fewer than 10 percent having side effects that require hospitalization. As compared to human chemotherapy protocols for similar cancers, many veterinary protocols are less intense. Our goal in veterinary oncology is to offer longer life for animal cancer patients, and to balance that with a good quality of life.

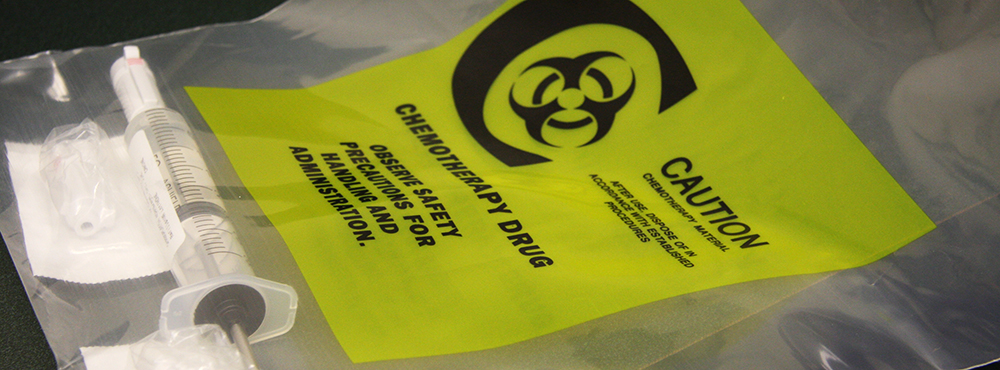

Some common chemotherapy agents used in the treatment of cancer include Adriamycin (doxorubicin), carboplatin, cisplatin, Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide), epirubicin, L-asparaginase, lomustine, mitoxantrone, Palladia (toceranib), prednisone, vinblastine, vincristine and vinorelbine.

Side effects common to most chemotherapy agents include bone marrow suppression (low blood cell counts, specifically infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils and blood clotting cells called platelets), gastrointestinal (stomach/gut) toxicity and alopecia (hair loss). Individual agents also have some unique toxicities, such as bloody urine with cyclophosphamide (sterile hemorrhagic cystitis), heart toxicity with doxorubicin (dilated cardiomyopathy) and kidney toxicity with cisplatin.

Hair loss affects relatively few of our patients. This is because animals’ coats grow to a certain length and then stop. Human hair is susceptible because it is constantly growing. Dogs with coats that need to be trimmed, such as poodles, terrier breeds and old English sheepdogs, will often lose hair during chemotherapy. Terrier breeds with fluffy, whiskered muzzles often lose their facial hair first. Most dogs will be slow to regrow hair where it has been shaved. Cats also tend not to lose their hair, but often will lose their whiskers. It is possible to start seeing hair loss after the first chemotherapy treatment.

Gastrointestinal toxicity generally manifests as nausea, vomiting or diarrhea. This can range from not finishing a meal to profuse vomiting and diarrhea requiring hospitalization to combat dehydration. Occasionally there is blood in the stool. These problems usually start within three days after treatment and last for three to five days.

For most drugs, bone marrow suppression is most significant approximately seven to 10 days following treatment. The bone marrow rebounds quickly, but for a few days the white blood cell counts (and sometimes platelet counts) are lower than normal. This is usually not a clinical problem, but if counts are low enough, the body lacks infection-fighting white blood cells and can be susceptible to infections anywhere in the body. This can include life-threatening problems such as pneumonia or blood infection (sepsis).

The reason we see these side effects with many drugs is that chemotherapy tends to target rapidly dividing cells, which is a characteristic of cancer cells. Therefore, cells in the body that normally have a rapid turnover, such as the bone marrow or the lining of the stomach and intestine, are also susceptible to injury.

Some drugs have unique toxicities that do not occur with other drugs, even with drugs with the same mechanism of action. Adriamycin (doxorubicin) can cause irreversible heart damage; Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide) can cause bloody urine. The incidence of these toxicities is relatively low.

More than 80 percent of patients tolerate side effects well enough to be managed at home. Anti-nausea and anti-diarrhea medication can help make our patients feel better during this time. Some patients need to be seen by a doctor but can be treated on an outpatient basis. Fewer than 10 percent of patients need to be hospitalized for side effects related to chemotherapy. Most of these patients will get better with prompt and aggressive therapy. It is possible for patients to die of complications of their chemotherapy, even with appropriate treatment, but this is rare. If your pet is undergoing chemotherapy and shows signs of illness, it is important to consult a veterinarian at least by phone initially, even if it is after hours, to see if medical attention is recommended.

Overall, most clients are satisfied with their decision to pursue chemotherapy. There are certain cancers in which repeated studies have shown a survival benefit with chemotherapy, such as lymphoma, osteosarcoma and hemangiosarcoma. There are many other cancers where response to chemotherapy has been promising, and still other cancers where chemotherapy is recommended based on the known behavior of the tumor despite a lack of studies to confirm its efficacy.

The most important part of deciding if your pet should undergo chemotherapy is to first identify your treatment goals. If you want to have as much time with your pet as possible, a more aggressive protocol may be the right decision. If your primary goal is that your pet not experience side effects, a less aggressive approach may be in order. No matter what you decide, if it is right for you and your pet, it is the right decision.

Establish a good basis for trust and communication with your veterinarian, and they will help guide your decisions. Be sure your veterinarian is comfortable giving chemotherapy and managing possible side effects, so that if your pet has difficulties, you know what channels to follow. Chemotherapy side effects can be made less severe in some patients with proper medication and supportive care. Along with your veterinarian and their staff, you are a critical member of your pet’s health care team.

Managing Chemotherapy Side Effects at Home

Although chemotherapy can cause side effects, there are things you can do to help your pet through the rough spots. It is important to remember that when your pet doesn’t feel well, you can usually help at home, but not always.

For stomach upset and diarrhea, initially rest your pet’s stomach by taking away all food and water for a few hours. If vomiting continues more than once during this period, call your veterinarian.

Once your pet has stopped vomiting for at least four hours, try offering small sips of water frequently. If your pet tolerates this, try small meals frequently (few tablespoons of food every few hours). Stick to foods that are gentle on the stomach (boiled chicken or ground beef and rice, or a low-fat dog food). Avoid treats and high-fat foods such as sausage, bacon or cheese.

There are anti-nausea and anti-diarrhea prescription medications that can be given preventively if your pet has difficulty with nausea or diarrhea. Continue to communicate and work with your oncology team to make the course of chemotherapy as comfortable as possible for both you and your pet.

When is it an Emergency?

Do not hesitate to contact the MU Veterinary Health Center, your local veterinarian or an animal emergency clinic if any of the following occur at any hour:

- Your pet does not respond to you

- Your pet runs a fever (for dogs this is generally greater than 103°F)

- Your pet vomits or has diarrhea more than three times per hour or three times per day

- You see blood in your pet’s vomit, stool or urine

- Your pet just doesn’t seem to be feeling well

Our Emergency and Critical Care Service is available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, but please call ahead to let them know you are on the way so they can be prepared to meet you on arrival. Call 573-882-7821 from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday or 573-882-4589 after hours.